In the “cooperation” agreement with Museveni’s party, Mao has set himself a target that will stiffly test his convening power, especially since he has been more divisive than uniting.

The moment the news of the appointment of the Democratic Party (DP) supremo Norbert Mao as Minister of Justice filtered through, I placed a phone call to Dr. Paul Kawanga Ssemogerere – or Ssemo in DP speak – a man who attended the early stages of Uganda’s oldest political party.

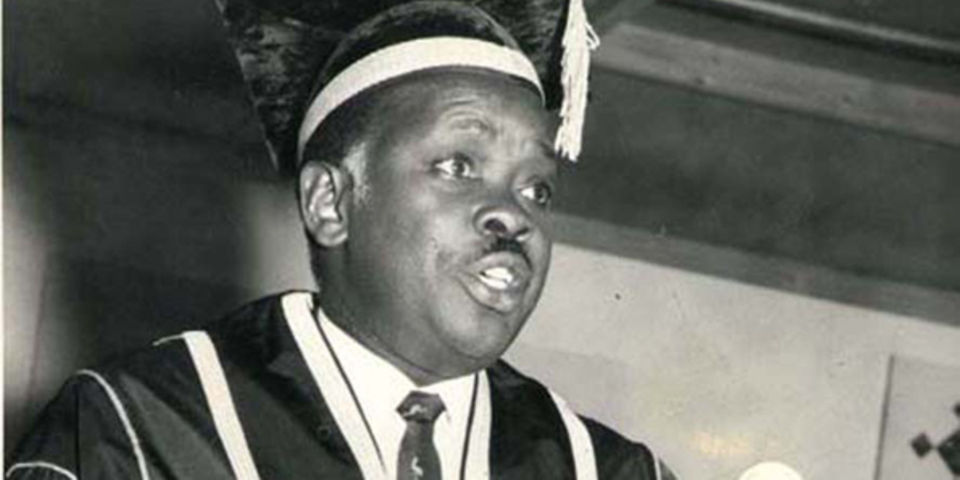

Ssemogerere, now 90 years old, retired from the leadership of DP in 2005, having been at its helm for 25 years, between 1980 and 2005, although political parties were heavily proscribed for most of that period. He worked closely with Benedicto Kiwanuka – fondly called Ben – who as leader of DP led the party to electoral victory in the pre-independence elections of 1961 and was Chief Minister until the elections of 1962 went against him.

Ssemogerere, closely serving under Kiwanuka, watched DP through acrimonious days with Buganda Kingdom and the party’s humiliation when its Leader of Opposition Basil Bataringaya crossed the floor along with five other MPs and joined the ruling Uganda Peoples Congress (UPC), which Milton Obote led. DP’s story got even harder when Idi Amin captured power and banned political activities, forcing its leader Kiwanuka to take up the job of Chief Justice in a system where laws mattered very little.

For his insistence on dispensing the law as it should be, Kiwanuka paid the ultimate price when he was dragged out of his chambers and disappeared without a trace. There are varying accounts of how he was killed and buried, and the exact place of his burial – whether in Luzira in Kampala or somewhere in Nakasongola – remains unknown. Ssemogerere would perhaps have been killed too if he had not escaped to the United States of America, only returning to Uganda after Amin was ousted to embark on remobilising the DP base.

In doing so, Ssemogerere reconciled the party with the Buganda Kingdom, which itself had been scattered by Obote’s 1966 invasion of the Kabaka’s palace at Mengo and forcing Kabaka Edward Mutesa II into exile in London, where he died in 1969. At different points, Obote had played and beaten DP and the Buganda Establishment, and since Obote had also returned from exile and was the candidate to beat in 1980, it cannot have been that hard for Ssemogerere to get Buganda behind him. His bid for the presidency in 1980 was nearly successful.

My phone call to Dr. Ssemogerere last week was to chat about Mao’s decision to join President Museveni’s government, but the nonagenarian statesman was not in the mood for such a conversation. “I would be moved if I had not seen so much,” Ssemogerere said, following up his statement with his signature laugh. He then told me the story of Bataringaya, the impressionable young man he met during his days as a student at Makerere University in the 1950s.

Benedicto Kagimu Kiwanuka, Uganda’s Chief Minister between 1961 and 1962.

The duo struck a friendship and Ssemogerere introduced Bataringaya to Kiwanuka, the leader of DP, and Bataringaya took to the party as fish does to water. Bataringaya rose to become DP secretary general and, after the 1962 elections which DP lost to the UPC-Kabaka Yekka alliance, became Leader of the Opposition in Parliament. Kiwanuka could not get to Parliament to lead the opposition because he hailed from Buganda where all constituencies were taken up by the Mengo party Kabaka Yekka.

Because Kiwanuka was not in Parliament where most of the politics happened, Bataringaya looked to undermine him and the party got so divided until Bataringaya decided to cross to UPC. After crossing the floor, Bataringaya was appointed Internal Affairs minister, and one of the notable things he did as minister was to sign a detention order that took Kiwanuka and Ssemogerere to prison without trial.

After the 1980 elections, which many accounts say were rigged against Ssemogerere and in Obote’s favour, Ssemogerere took up his position as Leader of the Opposition in Parliament, while many of his party members and supporters threw their weight behind those who took to military action, especially Museveni and the late Andrew Kayiira. To execute his war, Museveni heavily relied on well-educated young men who had come to the conclusion that Uganda’s politics could only be fixed by using force of arms to install a pro-people government that would embrace good governance and democracy.

Ssemogerere disagreed with this thinking, underlining the dangers that war would visit on Uganda and arguing that politics should be given a chance. Of all the intellectuals that followed Museveni to the bush, Dr. Kizza Besigye has been most vocal on regretting the act, and now says that political means must always be prioritised over war. He has christened Ssemogerere “the field marshal of Uganda’s politics”.

Ssemo’s dance with Museveni

In the wake of Mao’s marriage to Museveni’s government, parallels have been drawn with when Ssemogerere led a group of DP stalwarts to serve in Museveni’s first government in 1986. The former DP leader routinely tells the story of how Museveni sent Winnie Byanyima to invite him for a chat when the rebel leader, who was poised to take over power, was holed up in Nabbingo, just about a dozen kilometers from Kampala City centre.

Museveni’s choice of emissary was important, because Winnie was the daughter of Boniface Byanyima, a prominent DP leader. Ssemogerere had suffered under previous governments – targeted for physical annihilation by his fellow Baganda in the early 1960s, detained under Obote I, and forced into exile under Amin – and knew he did not have many choices in the volatile situation that obtained in the country.

At the time Museveni sent for him – January 1986 – power had all but slipped out of Tito Okello’s hold and it was apparent that Museveni would install himself as the new ruler soon. When Tito carried out a coup against Obote in mid-1985, his group had invited Ssemogerere to serve in Cabinet, and Ssemogerere had asked for the position of Internal Affairs Minister. Ssemogerere was also a member of the Tito government that negotiated a peace deal with Museveni in Nairobi, and had returned just before Christmas in 1985 in apparent triumph after Museveni’s group and the government of the day had signed a deal to end the fighting and share power. But, of course, Museveni later carried on with the fighting after signing on the dotted line to lay down arms, and would later refer to the Nairobi peace talks as “peace jokes”.

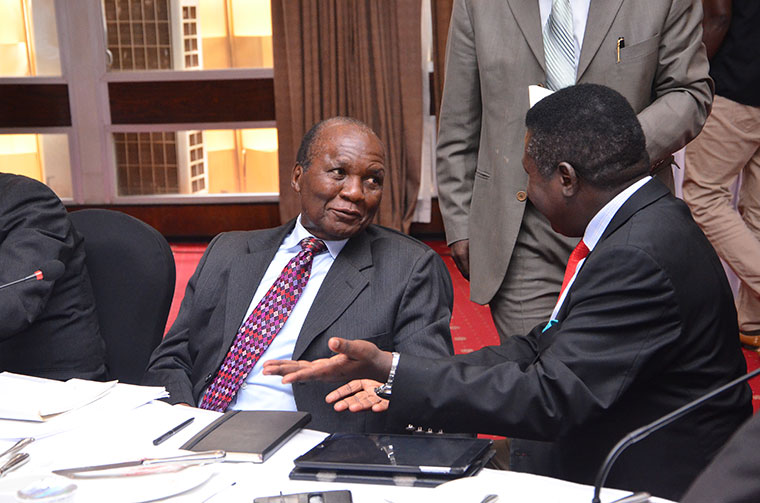

Dr. Paul Kawanga Ssemogerere (L) and Norbert Mao (R)

Before that, Museveni had played a trick on Ssemogerere and his group just after Prof. Yusuf Lule was overthrown as president in 1979. Museveni apparently tricked Ssemogerere and his colleagues, including Israel Mayengo, to relax upstairs at State House Entebbe in the false belief that no decision on whether to re-install Lule or who the new leader would be was to be reached without their involvement. What the group did not know, Mayengo says, was that Museveni and a few others had already arranged for Godfrey Binaisa to be installed as president.

So, when Ssemogerere went to Nabbingo to meet with Museveni. He had a good understanding of who he was meeting with, and what the results could be. But he did not have many options. And in the deal that was struck, Ssemogerere led a number of his party members to serve in Museveni’s government starting January 1986. Some of the prominent DP members who joined Ssemogerere in this episode were Evaristo Nyanzi, Robert Kitariko, John Ssebaana Kizito, Damiano Lubega and Joseph Mulenga.

Ssemogerere was again first appointed minister of Internal Affairs in Museveni’s government, a position he says would place him in good stead to do something about human rights violations and prevent things like detention without trial. Even when he was Leader of the Opposition in Parliament during Obote II, he also held the portfolio of shadow minister of Internal Affairs, which he says he used to persuade his opposite number and vice president Paulo Muwanga to release a number of detainees from police custody.

As Internal Affairs Minister under Museveni, Ssemogerere is proud that he stood up to the president and military officers like the late Gen. Aronda Nyakairima, who were pushing for the abolition of the Uganda Police Force so that the military would take full charge of guaranteeing law and order, in addition to defending the country. Museveni had destroyed the pre-existing army and replaced it with the one he had built, and had got the fighting forces that he annexed from groups that joined him to heed to his doctrine. He prided in what he called the discipline of his army, but he was not sure that what he called the “UPC police” could be reformed without first being disbanded and at least rebuilt.

Ssemogerere protested against this, and went globe-trotting in the search for help to equip and re-orient the police force, in the process getting sizeable assistance from Germany. Although it was evident that Museveni did not like the police force a lot, the rebel-cum-president let Ssemogerere win on that one, perhaps because he had bigger business to deal with as far as consolidating his power was concerned. He needed whoever he could get on his side, especially in the context that he had taken over power in a country that had had six presidents in eight short years between 1979 and 1986.

In joining up with Museveni, Ssemogerere entered what he routinely referred to as a “gentleman’s agreement” with the president to work on a return to political pluralism and democratic governance, which would be underpinned by the writing of a new liberal constitution. Museveni had initially promised to be in charge for a short four years, during which he had said a new constitution would be written and a return to civilian rule carried out. The four years flew by and there was no new constitution in place, and to people like Ssemogerere, it was understandable given the challenges that the new government had to surmount. Some other players took a different view and saw the proposal to extend Museveni’s initial period as unacceptable. Wasswa Ziritwawula, a DP member, resigned from the National Resistance Council, the equivalent of Parliament at the time, in protest.

The constitution was finally written in 1994-5, and many disagreements emerged, with Ssemogerere teaming up with some other players who wanted among other things a return to multiparty politics to oppose Museveni’s insistence on further entrenching monolithic rule through what he called the Movement System. Although he said every Ugandan was a member of the Movement by law, he also routinely referred to “the divisive partyists”, and the Movement Secretariat preferred certain individuals to be elected to the Constituent Assembly, which debated the constitution. By the time the 1995 constitution making process was done, the political differences between Museveni and Ssemogerere had become irreconcilable, and the DP leader summoned his party stalwarts who were serving with Museveni to follow him out of Museveni’s government. Some went back with him, some had found a new home under Museveni’s roof and stayed put.

Ssemogerere would challenge Museveni in the 1996 election, with political party activity still restricted to headquarters. But even then, he managed to conjure up a coalition that also brought some UPC luminaries into his fold, most notably Cecilia Ogwal. By the time that election happened, Museveni was already 10 years in power and looking to renew himself for the challenges that lay ahead.

Museveni used the campaigns to accuse Ssemogerere of trying to bring back Obote, who was at the time exiled in Zambia. Obote still lived rent-free in Museveni’s head, and a clause that barred Ugandans from running for president after they attained 75 years of age had been inserted in the constitution. Many said it was targeting Obote at the time, and when Museveni was due to make 75 ahead of the 2021 elections, the logic that got the clause into the constitution ceased to matter.

Enter Mao

By the time of the 1996 elections, Ssemogerere had almost done his part, was past his peak and ageing. A new generation of leaders was emerging, and Ssemogerere had started to look at the then DP publicity secretary Anthony Wagaba Ssekweyama as the man who would lead DP into the future. Ssekweyama was about 20 years younger than Ssemogerere and was looked at as Ssemogerere’s heir-apparent in DP circles, and by the time he tragically died in a car crash in the year 2000, many were already referring to him as a presidential aspirant ahead of the 2001 elections.

Mao is one of the others who had made a name by then, and his performance in the Sixth Parliament had catapulted him unto the national stage, with some saying he was one for the future. The much vaunted defeat that Mao visited on the late Brig. Nobel Mayombo in the Makerere University guild presidential race in 1990 was also often referred to, and it was fashionable to pontificate that a Mao-Mayombo race at the national level was possible. Mayombo died in 2007.

That was a time of relative political idealism under Museveni. Within the Movement and the military – around the turn of the century – there were discussions about Museveni not running again in 2001 even when the constitution still permitted him to contest for one more five-year term. Some insiders were complaining that the original ideals of the party were no longer being adhered to, and the “revolution” could be derailed if Museveni did not leave power sooner than later. Similar conversations had ensued even earlier, with some players uncomfortable with Museveni running in 1996 after being in power for 10 years. Museveni also in a way encouraged talk about his retirement by often loudly casting his gaze on the day he would retire to tending his cows in his village of Rwakitura.

As the end of Museveni’s rule seemed near and every interested player lined their cards, Mao also got to work to squeeze for himself a place in the sun. He was a member of DP but he did not fancy himself to have sufficient support to seek to lead it at the turn of the century, and therefore did not even try. Instead, he engaged in different initiatives that he thought would sharpen his influence and accentuate his chances.

One such initiative that Mao started was UB40 – Ugandans Below 40 – targeting the youth who he hoped to play against the older politicians. He heaped the blame for all that had gone wrong in Uganda on politicians who were born before Independence, and called on younger Ugandans to back him to correct the wrongs. In a number of his activities around the turn of the century, Mao worked more closely with Jacob Oulanyah and Aggrey Awori, who were both originally UPC members but ended up in NRM, than with fellow DP members.

The death of Ssekweyama too close to the 2001 elections left Ssemogerere with no fallback plan on who would represent DP in the presidential race, and the veteran politician had already decided against running again. There were DP members who wanted to fill the void, with the lawyer Francis Bwengye being one of them. He had disagreements with Ssemogerere and actually went ahead to compete in the 2001 elections, but Ssemogerere threw his weight behind Besigye, who had forced himself out of the army in a process that started by penning a document in 1999 that was heavily critical of Museveni’s handling of the affairs of state.

For Mao, the 2001 presidential election campaign passed quietly as he concentrated on his re-election bid for his second and what he told voters in the then Gulu Municipality would be his last term as their MP. He won re-election and lived to his promise of not running again for MP, and in 2005, the year Museveni accepted to reopen the political space and allowed parties to operate fully, Mao threw himself in the ring to replace Ssemogerere as DP leader. Ssemogerere was not in the running for the position and Mao would lose the seat to Ssebaana. After the loss, Mao brought the delegates conference to a standstill, accusing the party of being Ganda-centric and mobilising delegates from northern Uganda to not participate any further in the delegates conference.

In the end, Mao extracted some concessions from the party hierarchy and a deal to make him vice president for northern region and manager of Ssebaana’s campaign was struck. It is also said that Mao got Ssebaana to promise to cede to him the party’s presidency in five years’ time. And come 2010, Ssebaana teamed up with Mao and a coterie of young DP members to organise a controversial delegates conference in Mbale, where Mao was declared president of the party. A section of DP members, including Erias Lukwago, Samuel Lubega Mukaaku and Betty Nambooze, boycotted the Mbale delegates conference, saying that they were waiting for the conclusion of a reconciliation process that was being spearheaded by Ssemogerere and others like Prof. Frederick Ssempebwa.

L-R: Paul Ssemogerere, President Museveni, Former president Milton Obote

Mao’s critics within DP claimed that the process leading to his installation as party president in Mbale was bankrolled by Museveni, and the accusations have stuck to-date. As DP president, Mao was often accused of advancing his stay at the helm of the party by allying with the ruling party. For instance, since 2012, DP and UPC are the only opposition parties that managed to send representatives to the East African Legislative Assembly (EALA), helped by the majority ruling party MPs. Even for the upcoming election, the ruling party has already declared that its majority MPs will support DP and UPC members for the two EALA positions available for the opposition parties, meaning that the National Unity Platform (NUP), like the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) before it, will not be able to send a member to EALA.

Mao has also over the recent years been a pushy advocate of opposition parties cooperating with the ruling party and Museveni under the Inter-Party Cooperation for Dialogue (IPOD), and has acerbically criticised FDC and recently NUP over the matter. He accuses the two parties of taking the money distributed by the Electoral Commission, which he says was heavily increased following discussions under IPOD, which they refuse to fully participate in, or at all. NUP has outright refused to enroll as a member of IPOD.

FDC and NUP, on their part, contend that the money for political parties that have representation in Parliament is provided for under the Political Parties and Organisations Act, and is drawn from the Consolidated Fund with IPOD having nothing to do with it. Mao is particularly incensed that FDC and NUP, because they have bigger numbers of MPs, take more money out of the Shs35 billion packet available to all parties than DP, UPC and Jeema, which have not skipped a single IPOD summit with Museveni.

Seen through these lenses, Mao’s critics within the opposition say the cooperation between Museveni and Mao that became public last week was only formalised in a document, but has existed for many years, in almost the same way UPC under James Akena and Museveni/NRM have been cooperating. The important change now is that Mao and some other DP members have or will join Museveni’s government. Akena’s wife, Betty Amongi, has been in Museveni’s cabinet since 2016 despite remaining a UPC MP, but Akena has stuck to controversially holding on as UPC president and hasn’t taken up a cabinet position.

In “cooperating” with Museveni, Mao has looked the country in the eye and declared that he has stepped forward. He has spoken of “courage”, both on his part and Museveni’s, and says he will be the bridge and lead the country in a crusade to understand that Museveni should not be an enemy to demonise but a potential ally to engage, especially in a situation where there are not many alternatives. As Minister of Justice, Mao hopes to lead a national dialogue and engender constitutional reforms that will place the country in a good place to transition from Museveni’s nearly four-decade rule.

Those who have engaged with Museveni or seen him at work for long are understandably pessimistic and are allowed the liberty to laugh off Mao’s statements. Museveni has over the years co-opted individuals and groups just to grow his power without paying attention to much of what the co-opted may want to achieve, and if Mao ends up being ignored and frustrated within Museveni’s cobweb, there would be nothing new to write home about. Mao will just go down in history as one other man who, after he saw no other option to resuscitate his effectively dead political career built out of opposing Museveni, reached out to Museveni for a job and found a good way to justify it.

Mao must know that. But he is also aware that Museveni will soon be 80 years old and will hopefully be looking for a safe way to bring his long stay in power to an end. And being one of the newest in the ageing leader’s stable may stand Mao in good stead. That is a big IF, only contingent on whether Museveni is keen on arranging and controlling a transition and not let nature take its course. From within the ruling party, there have already been voices of discomfort at how Museveni ignores many of his long-suffering soldiers and invites to the high table those who have always been opposing him.

Beside that, there is also serious baggage that Mao arrives in Museveni’s cabinet with. In the recent past, he launched what he called a “one-man army” war against NUP, and said many things about the party and its leader Robert Kyagulanyi, including that the party should be de-registered because it was not legally acquired. He said this despite the High Court deciding that very matter in NUP’s favour hardly two years ago.

Mao, as already pointed out, has also spent many years in confrontation with FDC and Besigye, and is not well liked by a number of other politicians even from Acholi ethnic group. For instance, Prof. Ogenga Latigo said in the wake of Mao’s cooperation agreement coming to light that Mao does not consult and that when they were both in Parliament, they removed Mao from the leadership of the Acholi Parliamentary Group because he often took decisions unilaterally.

Within his own DP, Mao faces a revolt as a number of players have vowed to kick him out of the party’s leadership for purporting to enter an agreement on behalf of the party without consulting its key organs. Mao must have anticipated this backlash, and weeks before his deal with Museveni became public, he sent some money to all party branches in all districts. It is not clear how much work he is doing under the radar, and his critics within the party may be surprised. In any case, he has some jobs, including one for minister of state and top executive positions in government authorities and corporations to dangle at some of the people who may want to cause him trouble.

But be that as it may, it is clear that Mao’s convening power will get stiffly tested if he ever gets to spearhead a national dialogue like the one he wrote into the “cooperation agreement” with the ruling party.

As leader of DP, Mao has often said that he is able to see far because he stands on shoulders of giants, citing Ben Kiwanuka and in fewer circumstances Ssemogerere. In his quest to consolidate his hold on DP, Mao even tried to appeal to nostalgia and launched an unsuccessfully search for Kiwanuka’s remains “to give him a decent burial”. He also likes to throw around the artistic impression of the “Ben Kiwanuka House” that he dreams of, which would be the headquarters of DP.

But most of the things Mao has tried to do as president of DP have not helped him to gain the significant support among the party faithful, and following the marriage he has entered into with the ruling party, he will most likely need military guard at his DP offices. That is why he will be desperate to extract from Museveni what no other player has ever achieved, and also be able to use the “cooperation” to improve the fortunes of at least DP, if not Uganda.